As you might know, the Marten core team is in the process of building a new business around the “Critter Stack” tools (Marten + Wolverine and a couple smaller things). I think we’ll shortly be able to offer formal paid support contracts through JasperFx Software, and we’re absolutely open for business for any kind of immediate consulting on your software initiatives.

Call this a follow up from the Critter Stack roadmap from back in March. Everything takes longer than you wish it would, but at least Wolverine went 1.0 and I’m happy with how that’s been received so far and its uptake.

In the immediate future, we’re kicking out a Marten 6.1 release with a new health check integration and some bug fixes. Shortly afterward, we hope to get another 6.1.1 release out with as many bug fixes as we can address quickly to clear the way for the next big release. With that out of the way, let’s get on to the big initiatives for Marten!

Marten 7 Roadmap

Marten 6 was a lot of bug fixing and accommodating the latest version of Npgsql, our dependency for low level communication with PostgreSQL. Marten 7 is us getting on track for our strategic initiatives. Right now the goal is to move to an “open core” model for Marten where the current library and its capabilities stay open and free, but we will be building more advanced features for bigger workloads in commercial add on projects.

For the open core part of Marten, we’re aiming for:

- Significant improvements to the LINQ provider support for better performing SQL and knocking down an uncomfortably long list of backlogged LINQ related issues and user requests. You can read more about that in Marten Linq Provider Improvements. Honestly, I think this is likely more work than the rest of the issues combined.

- Maybe adding Strong Typed Identifiers as a logical follow on to the LINQ improvements. It’s been a frequent request, and I can see some significant opportunities for integration with Wolverine later

- First class subscriptions in the event sourcing. This is going to be simplistic model for you to build your own persistent subscriptions to Marten events that’s a little more performant and robust than the current “IProjection for subscriptions” approach. More on this in the next section.

- A way to parallelize the asynchronous projections in Marten for improved scalability based on Oskar’s strategy described in Scaling Marten.

- .NET 8 integration. No idea what if anything that’s going to do to us.

- Incorporating Npgsql 8. Also no idea if that’s going to be full of unwanted surprises or a walk in the park yet

- A lightweight option for partial updates of Marten documents. We support this through our PLv8 add on, but that’s likely being deprecated and this comes up quite a bit from people moving to Marten from MongoDb

Critter Stack Enterprise-y Edition

Now, for the fun part, the long planned, long dreamed of commercial add ons for true enterprise Critter Stack usage. We have initial plans to build an all new library using both Marten and Wolverine that will be available under a commercial subscription.

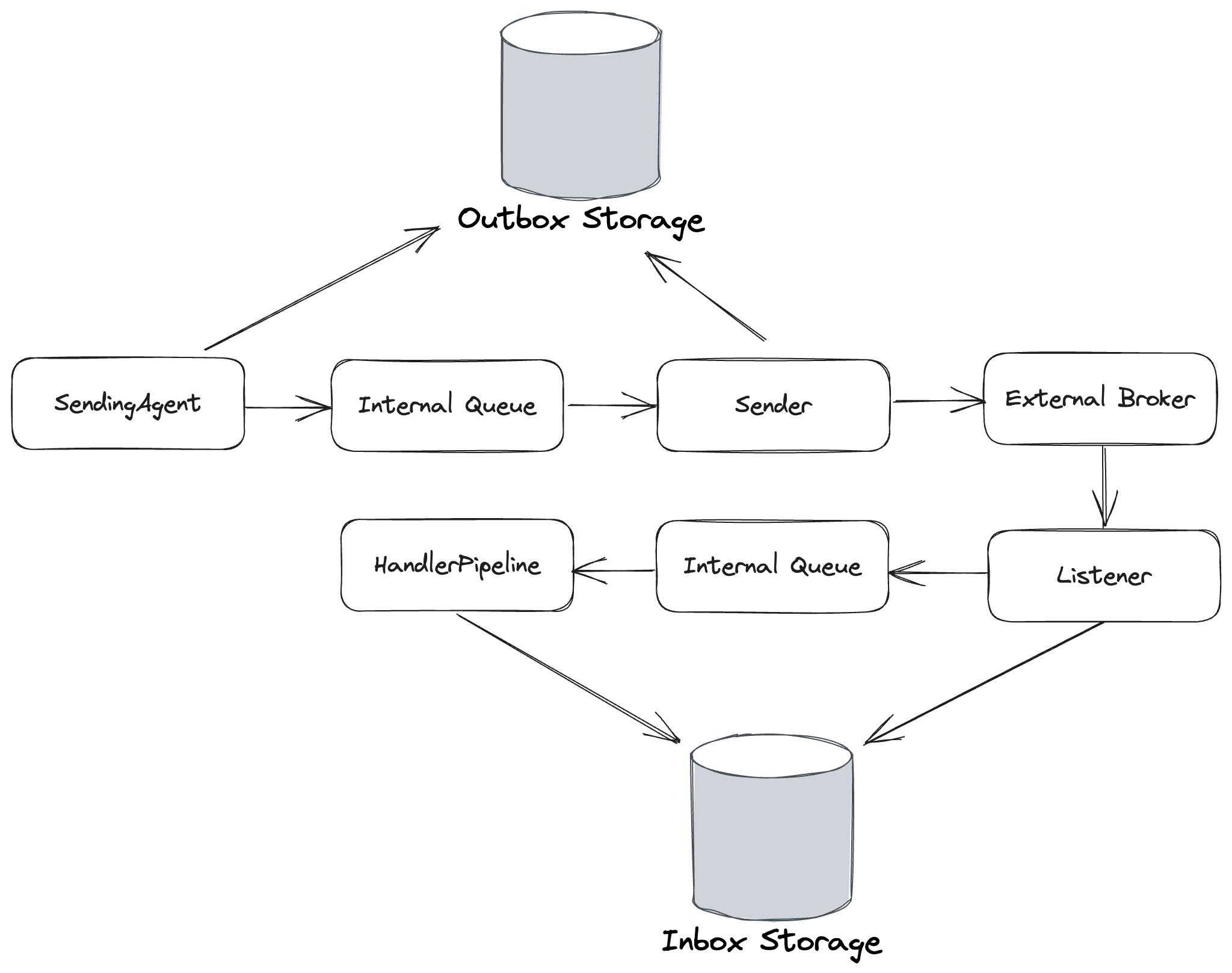

Projection Scalability

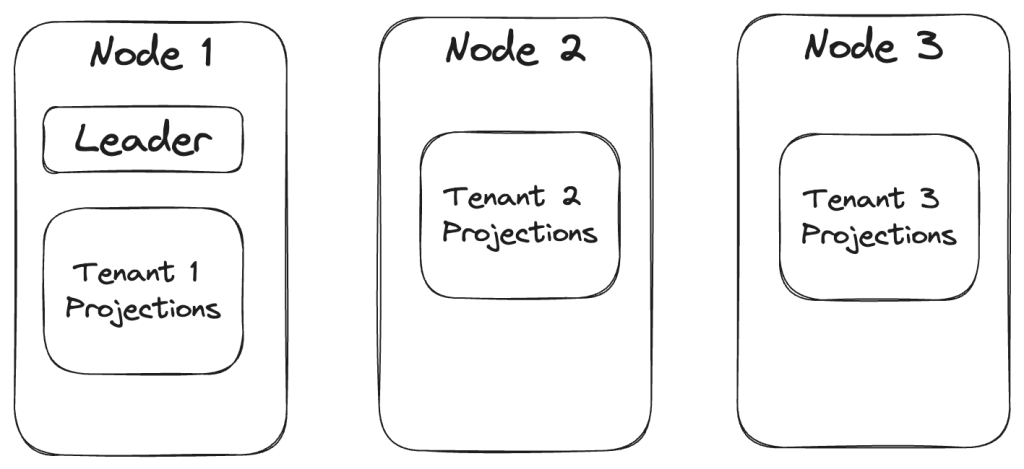

Most of the biggest issues with scaling Marten to bigger systems are related to the asynchronous projection support. The first goal is scalability through distributing projection work across all the running nodes within your application. Wolverine already has leader election and “agent assignment” functionality that was built with this specific need in mind. To make that a little more clear, let’s say that you’re using Marten with a database per tenant multi-tenancy strategy. With “Critter Stack Enterprise” (place holder until we get a better name), the projection work might be distributed across nodes by tenant something like this:

The “leader agent” would help redistribute work as nodes come online or offline.

Improving scalability by distributing load across nodes is a big step, but there’s more tricks to play with projection throughput that would be part of this work.

Zero Downtime, Blue/Green Deployments

With the new projection daemon alternative, we will also be introducing a new “blue/green deployment” scheme where you will be able to change existing projections, introduce all new projections, or introduce new event signatures without having to have a potentially long downtime for rebuilding projections the way you might have to with Marten today. I feel like we have some solid ideas for how to finally pull this off.

More Robust Subscription Recipes

I don’t have many specifics here, but I think there’s an opportunity to also support more robust subscription offerings out of the Marten events using existing or new Wolverine capabilities. I also think we can offer stricter ordering and delivery guarantees with the Marten + Wolverine combination than we ever could with Marten alone. And frankly, I think we can do something more robust than what our obvious competitor tools do today.

Additional Event Store Throughput Improvements

Some other ideas we’re kicking around:

- Introduce 2nd level caching into the aggregation projections

- Elastic scalability for rebuilding projections

- Hot/cold event store archiving that could improve both performance and scalability

- Optional usage of higher performance serializers in the event store. That mostly knocks out LINQ querying for the event data

Other Stuff

We have many more ideas, but I think that the biggest theme is going to be ratcheting up the scalability of the event sourcing functionality and CQRS usage in general. There’s also a possibility of taking Marten’s event store functionality into cross-platform usage this year as well.

Thoughts? Requests? Wanna run jump in line to hire JasperFx Software?