After over a year of work, I’m finally getting close to making an official 3.0 release of the newly rebuilt Storyteller project for executable specifications (BDD). There’s a webinar on youtube that I got to record for JetBrains for more background.

As a specification tool, Storyteller shines when the problem domain you’re working in lends itself toward table based specifications. At the same time, we’ve also invested heavily in making Storyteller mechanically efficient for expressing test data inputs with tables and the ability to customize data parsing in the specifications.

For an example, I’ve been working on a small OSS project named “Alba” that is meant to be a building block for a future web framework. Part of that work is a new HTTP router based on the Trie algorithm. One of our requirements for the new routing engine was to be able to detect routes with or without parameters (think “document/:id” where “id” is a routing parameter) and to be able to accurately match routes regardless of what order the routes were added (ahem, looking at you old ASP.Net Routing Module).

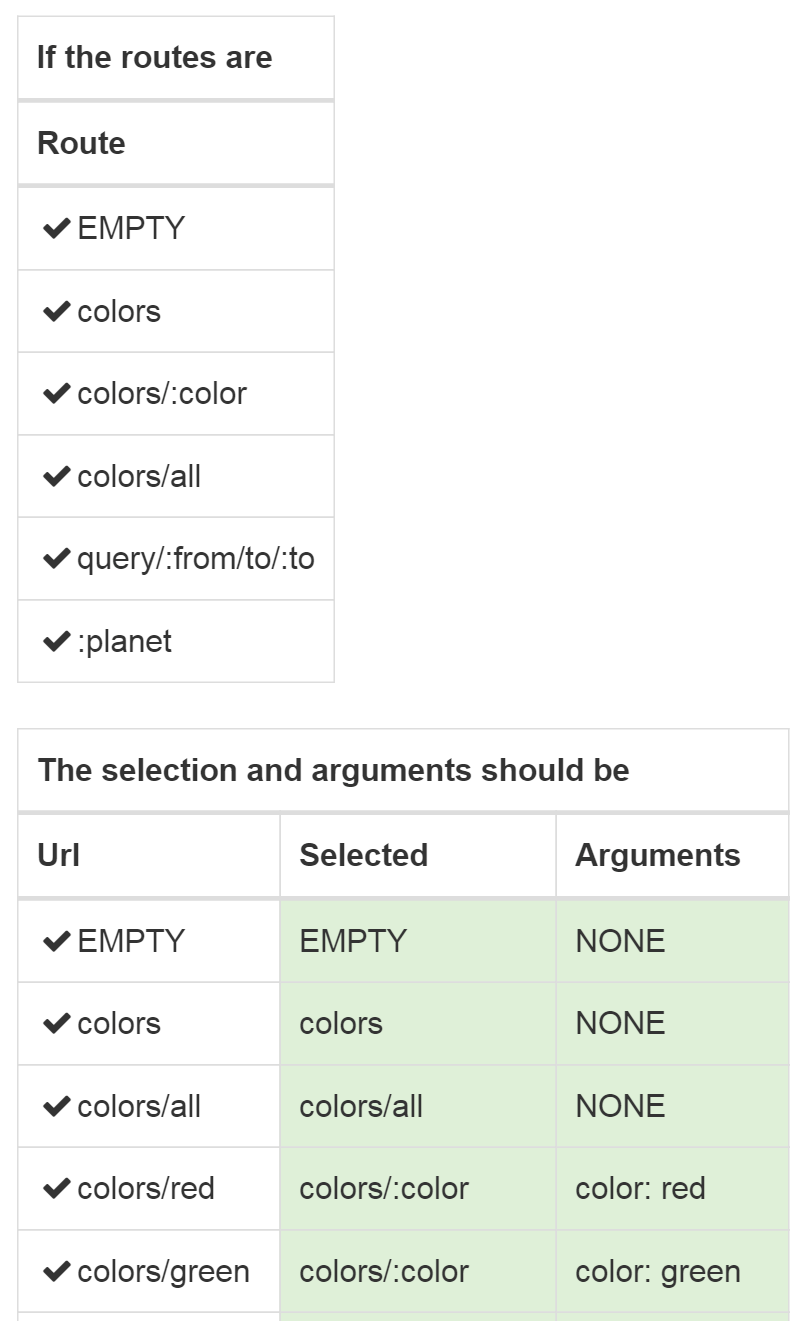

This turns out to be a pretty natural fit for expressing the requirements and sample scenarios with Storyteller. I started by jotting some notes on how I wanted to express the specifications by first setting up all the available routes in a new instance of the router, then running a series of scenarios through the router and proving that the router was choosing the correct route pattern and determining the route arguments for the routes that have parameters. That results of one of the specifications for the routing engine is shown below (but cropped for space):

Looking at the spec above, I did a couple things.

- “If the routes are” is a table grammar that just configures a router object with the supplied routes

- “The selection and arguments should be” is a second table grammar that takes in a Url pattern as an input, then asserts expected values against the route that was matched in the “Selected” column and uses a custom assertion to match up on the route parameters parsed from the Url (or asserts that there was “NONE”).

To set up the routing table in the first place, the “If the routes are” grammar is this (with the Fixture setup code to add some necessary context”:

// This runs silently as the first step of a

// section using this Fixture

public override void SetUp()

{

_tree = new RouteTree();

}

[ExposeAsTable("If the routes are")]

public void RoutesAre(string Route)

{

var route = new Route(Route, HttpVerbs.GET, _ => Task.CompletedTask);

_tree.AddRoute(route);

}

The table for verifying the route selection is implemented by a second method:

[ExposeAsTable("The selection and arguments should be")]

public void TheSelectionShouldBe(

string Url,

out string Selected,

[Default("NONE")]out ArgumentExpectation Arguments)

{

var env = new Dictionary<string, object>();

var leaf = _tree.Select(Url);

Selected = leaf.Pattern;

leaf.SetValues(env, RouteTree.ToSegments(Url));

Arguments = new ArgumentExpectation(env);

}

The input value is just a single string “Url.” The method above takes that url string, runs it through the RouteTree object we had previously configured (“If the routes are”), finds the selected route, and fills the two out parameters. Storyteller itself will compare the two out values to the expected values defined by the specification. In the case of “Selected”, it just compares two strings. In the case of “ArgumentExpectation”, that’s a custom type I built in the Alba testing library as a custom assertion for this grammar. The key parts of ArgumentExpectation are shown below:

private readonly string[] _spread;

private readonly IDictionary<string, object> _args;

public ArgumentExpectation(string text)

{

_spread = new string[0];

_args = new Dictionary<string, object>();

if (text == "NONE") return;

var args = text.Split(';');

foreach (var arg in args)

{

var parts = arg.Trim().Split(':');

var key = parts[0].Trim();

var value = parts[1].Trim();

if (key == "spread")

{

_spread = value == "empty"

? new string[0]

: value.Split(',')

.Select(x => x.Trim()).ToArray();

}

else

{

_args.Add(key, value);

}

}

}

public ArgumentExpectation(Dictionary<string, object> env)

{

_spread = env.GetSpreadData();

_args = env.GetRouteData();

}

protected bool Equals(ArgumentExpectation other)

{

return _spread.SequenceEqual(other._spread)

&& _args.SequenceEqual(other._args);

}

Storyteller provides quite a bit of customization on how the engine can convert a string to the proper .Net type for any particular “Cell.” In the case of ArgumentExpectation, Storyteller has a built in convention to use any constructor function with the signature “ctor(string)” to convert a string to the specified type and I exploit that ability here.

You can find all of the code for the RoutingFixture behind the specification above on GitHub. If you want to play around or see all of the parts of the specification, you can run the Storyteller client for Alba by cloning the Github repository, then running the “storyteller.cmd” file to compile the code and open the Storyteller client to the Alba project.

Why was this useful?

Some of you are rightfully reading this and saying that many xUnit tools have parameterized tests that can be used to throw lots of test scenarios together quickly. That’s certainly true, but the Storyteller mechanism has some advantages:

- The test results are shown clearly and inline with the specification html itself. It’s not shown above (because it is a regression test that’s supposed to be passing at all times;-)), but failures would be shown in red table cells with both the expected and actual values. This can make specification failures easier to understand and diagnose compared to the xUnit equivalents.

- Only the test inputs and expected results are expressed in the specification body. This makes it substantially easier for non technical stakeholders to more easily comprehend and review the specifications. It also acts to clearly separate the intent of the code from the mechanical details of the API. In the case of the Alba routing engine, that is probably important because the implementation today is a little tightly coupled to OWIN hosting but it’s somewhat likely we’d like to decouple the router from OWIN later as ASP.Net seems to be making OWIN a second class citizen from here on out.

- The Storyteller specifications or their results can be embedded into technical documentation generated by Storyteller. You can see an example of that in the Storyteller docs themselves.

- You can also add prose in the form of comments to the Storyteller specifications for more descriptions on the desired functionality (not shown here).