It’s early so I should be too cocky, but JasperFx Software is having success in integrating SignalR with both Wolverine and Marten in our forthcoming CritterWatch product. In this post I’ll show you how we’re doing that from the server side C# code all the way down to the client side TypeScript.

Last week I did a live stream talking about many of the details and a way too early demonstration of CritterWatch, JasperFx Software‘s long planned management console for the “Critter Stack” tools (Marten, Wolverine, and soon to be Polecat).

A big technical wrinkle in the CritterWatch approach so far is our utilization of the SignalR messaging support built into Wolverine. Just like with external messaging brokers like Rabbit MQ or Azure Service Bus, Wolverine does a lot of work to remove the technical details of SignalR and let’s you focus on just writing your application code.

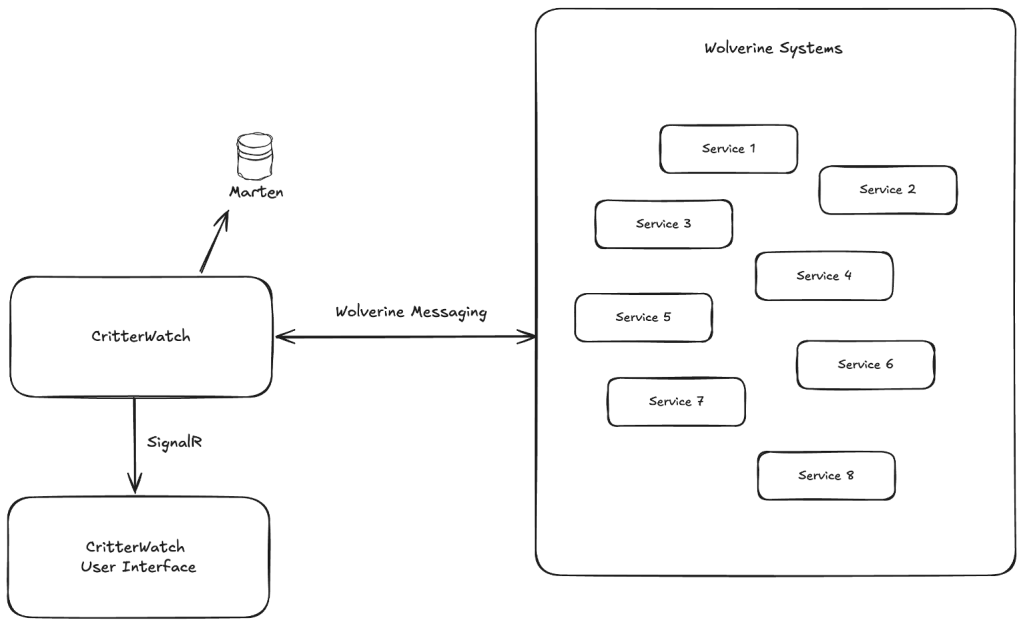

In some ways, CritterWatch is kind of a man in the middle between the intended CritterWatch user interface (Vue.js) and the Wolverine enabled applications in your system:

Note that Wolverine will be required for CritterWatch, but if you only today use Marten and want to use CritterWatch to manage just the event sourcing, know that you will be able to use a very minimalistic Wolverine setup just for communication to CritterWatch without having to migrate your entire messaging infrastructure to Wolverine. And for that matter, Wolverine now has a pretty robust HTTP transport for asynchronous messaging that would work fine for CritterWatch integration.

As I said earlier, CritterWatch is going to depend very heavily on two way WebSockets communication between the user interface and the CritterWatch server, and we’re utilizing Wolverine’s SignalR messaging transport (which was purposefully built for CritterWatch in the first place) to get that done. In the CritterWatch codebase, we have this little bit of Wolverine configuration:

public static void AddCritterWatchServices(this WolverineOptions opts, NpgsqlDataSource postgresSource)

{

// Much more of course...

opts.Services.AddWolverineHttp();

opts.UseSignalR();

// The publishing rule to route any message type that implements

// a marker interface to the connected SignalR Hub

opts.Publish(x =>

{

x.MessagesImplementing<ICritterStackWebSocketMessage>();

x.ToSignalR();

});

// Really need this so we can handle messages in order for

// a particular service

opts.MessagePartitioning.UseInferredMessageGrouping();

opts.Policies.AllListeners(x => x.PartitionProcessingByGroupId(PartitionSlots.Five));

}And at the bottom of the ASP.Net Core application hosting CritterWatch, we’ll have this to configure the request pipeline:

builder.Services.AddWolverineHttp();var app = builder.Build();// Little bit more in the real code of course...app.MapWolverineSignalRHub("/api/messages");return await app.RunJasperFxCommands(args);As you can infer from the Wolverine publishing rule above, we’re using a marker interface to let Wolverine “know” what messages should always be sent to SignalR:

/// <summary>/// Marker interface for all messages that are sent to the CritterWatch web client/// via web sockets/// </summary>public interface ICritterStackWebSocketMessage : ICritterWatchMessage, WebSocketMessage;We also use that marker interface in a homegrown command line integration to generate TypeScript versions of all those messages with NJsonSchema as well as message types that go from the user interface to the CritterWatch server. Wolverine’s SignalR integration assumes that all messages sent to SignalR or received from SignalR are wrapped in a Cloud Events compliant JSON wrapper, but the only required members are type that should identify what type of message it is and data that holds the actual message body as JSON. To make this easier, when we generate the TypeScript code we also insert a little method like this that we can use to identify the message type sent from the client to the Wolverine powered back end:

export class CompactStreamResult implements WebsocketMessage { serviceName!: string; streamId!: string; success!: boolean; error!: string | undefined; queryId!: string | undefined; // THIS method is injected by our custom codegen // and helps us communicate with the server as // this matches Wolverine's internal identification of // this message get messageTypeName() : string{ return "compact_stream_result"; } // other stuff... init(_data?: any) { if (_data) { this.serviceName = _data["serviceName"]; this.streamId = _data["streamId"]; this.success = _data["success"]; this.error = _data["error"]; this.queryId = _data["queryId"]; } } static fromJS(data: any): CompactStreamResult { data = typeof data === 'object' ? data : {}; let result = new CompactStreamResult(); result.init(data); return result; } toJSON(data?: any) { data = typeof data === 'object' ? data : {}; data["serviceName"] = this.serviceName; data["streamId"] = this.streamId; data["success"] = this.success; data["error"] = this.error; data["queryId"] = this.queryId; return data; }}Most of the code above is generated by NJsonSchema, but our custom codegen inserts in the get messageTypeName() method, that we use in the client side code below to wrap up messages to send back up to our server:

async function sendMessage(msg: WebsocketMessage) {

if (conn.state === HubConnectionState.Connected) {

const payload = 'toJSON' in msg ? (msg as any).toJSON() : msg

const cloudEvent = JSON.stringify({

id: crypto.randomUUID(),

specversion: '1.0',

type: msg.messageTypeName,

source: 'Client',

datacontenttype: 'application/json; charset=utf-8',

time: new Date().toISOString(),

data: payload,

})

await conn.invoke('ReceiveMessage', cloudEvent)

}

}In the reverse direction, we receive the raw message from a connected WebSocket with the SignalR client, interrogate the expected CloudEvents wrapper, figure out what the message type is from there, deserialize the raw JSON to the right TypeScript type, and generally just relay that to a Pinia store where all the normal Vue.js + Pinia reactive user interface magic happens.

export function relayToStore(data: any){ const servicesStore = useServicesStore(); const dlqStore = useDlqStore(); const metricsStore = useMetricsStore(); const projectionsStore = useProjectionsStore(); const durabilityStore = useDurabilityStore(); const eventsStore = useEventsStore(); const scheduledMessagesStore = useScheduledMessagesStore(); const envelope = typeof data === 'string' ? JSON.parse(data) : data; switch (envelope.type){ case "dead_letter_details": dlqStore.handleDeadLetterDetails(DeadLetterDetails.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "dead_letter_queue_summary_results": dlqStore.handleDeadLetterQueueSummaryResults(DeadLetterQueueSummaryResults.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "all_service_summaries": const allSummaries = AllServiceSummaries.fromJS(envelope.data); servicesStore.handleAllServiceSummaries(allSummaries); if (allSummaries.persistenceCounts) { for (const pc of allSummaries.persistenceCounts) { durabilityStore.handlePersistenceCountsChanged(pc); } } if (allSummaries.metricsRollups) { metricsStore.handleAllMetricsRollups(allSummaries.metricsRollups); } break; case "summary_updated": servicesStore.handleSummaryUpdated(SummaryUpdated.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "agent_and_node_state_changed": servicesStore.handleAgentAndNodeStateChanged(AgentAndNodeStateChanged.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "service_summary_changed": servicesStore.handleServiceSummaryChanged(ServiceSummaryChanged.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "metrics_rollup": metricsStore.handleMetricsRollup(MetricsRollup.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "all_metrics_rollups": metricsStore.handleAllMetricsRollups(AllMetricsRollups.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "shard_states_changed": projectionsStore.handleShardStatesChanged(ShardStatesChanged.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "persistence_counts_changed": durabilityStore.handlePersistenceCountsChanged(PersistenceCountsChanged.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "stream_details": eventsStore.handleStreamDetails(StreamDetails.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "event_query_results": eventsStore.handleEventQueryResults(EventQueryResults.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; case "compact_stream_result": eventsStore.handleCompactStreamResult(CompactStreamResult.fromJS(envelope.data)); break; // *CASE ABOVE* -- do not remove this comment for the codegen please! }}And that’s really it. I omitted some of our custom codegen code (because it’s hokey), but it doesn’t do much more than find the message types in the .NET code that are marked as going to or coming from the Vue.js client and writes them as matching TypeScript types.

But wait, Marten gets into the act too!

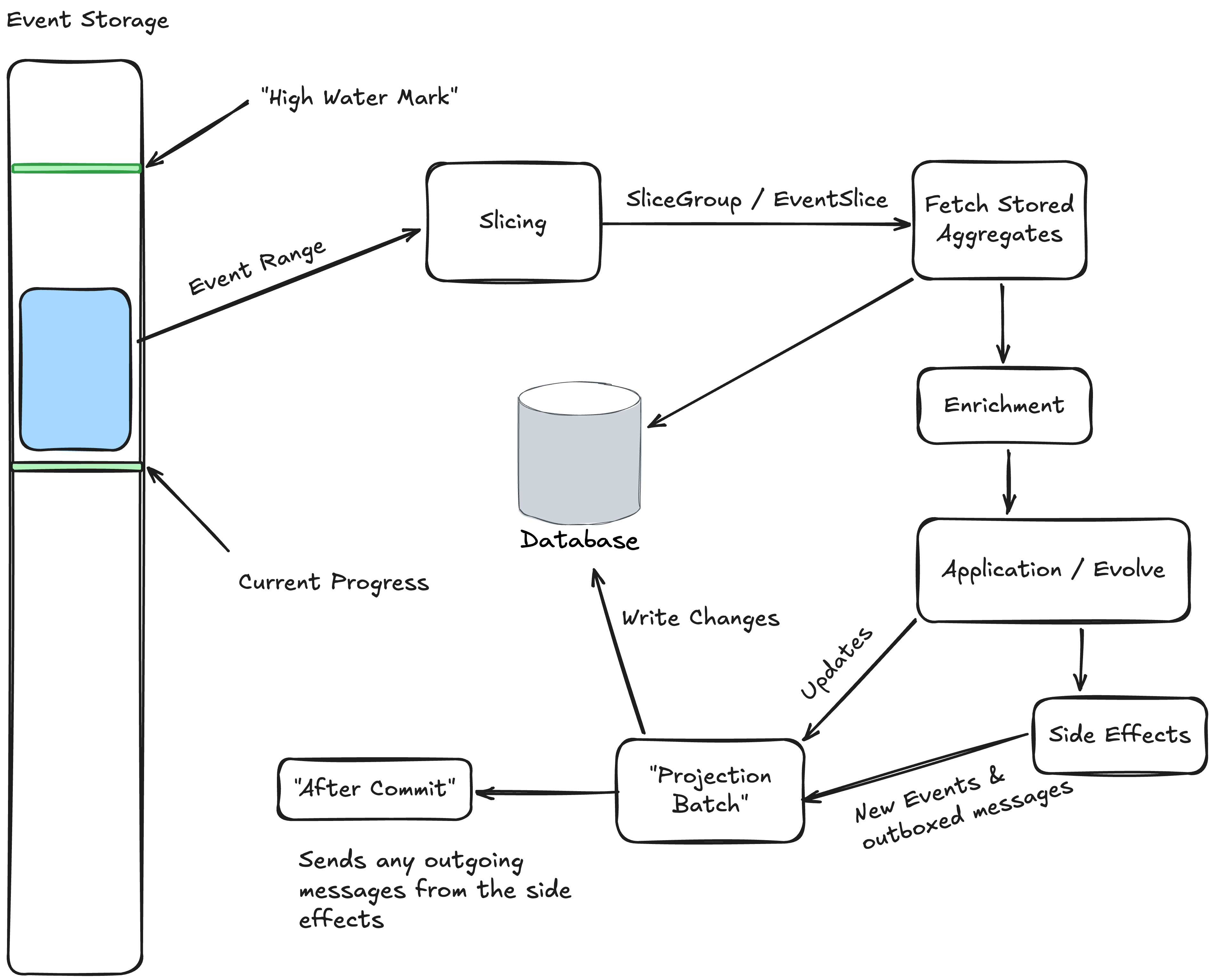

With the Marten + Wolverine integration through this:

opts.Services.AddMarten(m =>

{

// Other stuff...

m.Projections.Add<ServiceSummaryProjection>(ProjectionLifecycle.Async);

}).IntegrateWithWolverine(w =>

{

w.UseWolverineManagedEventSubscriptionDistribution = true;

});Marten can also get into the SignalR act through its support for “Side Effects” in projections. As a certain projection for ServiceSummary is updated with new events in CritterWatch, we can raise messages reflecting the new changes in state to notify our clients with code like this from a SingleStreamProjection:

public override ValueTask RaiseSideEffects(IDocumentOperations operations, IEventSlice<ServiceSummary> slice)

{

var hasShardStates = slice.Events().Any(x => x.Data is ShardStatesUpdated);

if (hasShardStates)

{

var shardEvent = slice.Events().Last(x => x.Data is ShardStatesUpdated).Data as ShardStatesUpdated;

slice.PublishMessage(new ShardStatesChanged(slice.Snapshot.Id, shardEvent!.States));

}

if (slice.Events().All(x => x.Data is IImpactsAgentOrNodes || x.Data is ShardStatesUpdated))

{

if (!hasShardStates)

{

slice.PublishMessage(new AgentAndNodeStateChanged(slice.Snapshot.Id, slice.Snapshot.Nodes, slice.Snapshot.Agents));

}

}

else

{

slice.PublishMessage(new ServiceSummaryChanged(slice.Snapshot));

}

return new ValueTask();

}The Marten projection itself knows absolutely nothing about where those messages will go or how, but Wolverine kicks in to help its Critter Stack sibling and it deals with all the message delivery. The message types above all implement the ICritterStackWebSocketMessage interface, so they will get routed by Wolverine to SignalR. To rewind, the workflow here is:

- CritterWatch constantly receives messages from Wolverine applications with changes in state like new messaging endpoints being used, agents being reassigned, or nodes being started or shut down

- CritterWatch saves any changes in state as events to Marten (or later to SQL Server backed Polecat)

- The Marten async daemon processes those events to update CritterWatch’s

ServiceSummaryprojection - As pages of events are applied to individual services, Marten calls that

RaiseSideEffects()method to relay some state changes to Wolverine, which will.. - Send those messages to SignalR based on Wolverine’s routing rules and on to the client side code which…

- Relays the incoming messages to the proper Pinia store

Summary

I won’t say that using Wolverine for processing and sending messages via SignalR is justified in every application, but it more than pays off if you have a highly interactive application that sends any number of messages between the user interface and the server.

Sometime last week I said online that no project is truly a failure if you learned something valuable from that effort that could help a later project succeed. When I wrote that I was absolutely thinking about the work shown above and relating that to a failed effort of mine called Storyteller (Redux + early React.js + roll your own WebSockets support on the server) that went nowhere in the end, but taught me a lot of valuable lessons about using WebSockets in a highly interactive application that has directly informed my work on CritterWatch.