In my last post on Automated Testing of Message Based Systems, I talked about how we are able to collapse all the necessary pieces of distributed messaging systems down to a single process and why I think that makes for a much better test automation experience. Once you can reliably bootstrap, tear down, and generally control your distributed application from a test harness, you move on to a couple more problems: when is a test actually done and what the heck is going on inside my system during the test when messages are zipping back and forth?

Knowing when to Assert in the Asynchronous World

Since everything is asynchronous, how does the test harness know when it’s safe to start checking outcomes? Any automated test is more or less going to follow the basic “arrange, act, assert” structure. If the “act” part of the test involves asynchronous operations, your test harness has to know how to wait for the “act” to finish before doing the “assert” part of a test in order for the tests to be reliable enough to be useful inside of continuous integration builds.

For a very real scenario, consider a test that involves:

- A website application that receives an HTTP POST, then sends a message through the service bus for asynchronous processing

- A headless service that actually processes the message from step 1, and quite possibly sends related messages to the service bus that also need to be finished processing before the test can do its assertions against expected change of state.

- The headless service may be sending messages back to the website application

To solve this problem in our test automation, we came up with the “MessageHistory” concept in FubuMVC’s service bus support to help order test assertions after all message processing is complete. When activated, MessageHistory allows our test harnesses to know when all message processing has been completed in a test, even when multiple service bus applications are taking part in the messaging work.

When a FubuMVC application has the service bus feature enabled, you can activate the MessageHistory feature by first bootstrapping in the “Testing” mode like so:

public class ChainInvokerTransportRegistry

: FubuTransportRegistry<ChainInvokerSettings>

{

public ChainInvokerTransportRegistry()

{

// This property opts the application into

// the "testing" mode

Mode = "testing";

// Other configuration declaring how the application

// is composed.

}

}

In a blog post last week, I talked about How we do Semantic Logging, specifically how we’re able to programmatically add listeners for strong typed audit or debug messages. By setting the “Testing” mode, FubuMVC adds a new listener called MessageRecordListener to the logging that listens for logging messages related to the service bus message handling. The method below from MessageRecordListener opts the listener into any logging message that inherits from the MessageLogRecord class we use to mark messages related to service bus processing:

public bool ListensFor(Type type)

{

return type.CanBeCastTo<MessageLogRecord>();

}

For the purposes of the MessageHistory, we listen for:

- EnvelopeSent — history of a message that was sent via the service bus

- MessageSuccessful or MessageFailed — history of a message being completely handled

- ChainExecutionStarted — a message is starting to be executed internally

- ChainExecutionFinished — a message has been completely executed internally

All of these logging messages have the message correlation id, and by tracking the outstanding “activity started” messages against the “activity finished” messages, MessageHistory can “know” when the message processing has completed and it’s safe to start processing test assertions. Even if an automated test involves multiple applications, we can still get predictable results as long as every application is logging its information to the static MessageHistory class (I’m not showing it here, but we do have a mechanism to connect message activity back to MessageHistory when we use separate AppDomain’s in tests).

Just to help connect the dots, the MessageRecordListener relays information about work that’s started or finished to MessageHistory with this method:

public void DebugMessage(object message)

{

var log = message.As<MessageLogRecord>();

var record = log.ToRecord();

if (record.IsPollingJobRelated()) return;

// Tells MessageHistory about the recorded

// activity

MessageHistory.Record(log);

_session.Record(record);

}

Inside of test harness code, the MessageHistory usage is like this:

MessageHistory.WaitForWorkToFinish(() => {

// Do the "act" part of your test against a running

// FubuMVC service bus application or applications

}).ShouldBeTrue();

This method does a couple things:

- Clears out any existing message history inside of MessageHistory so you’re starting from a blank slate

- Executes the .Net Action “continuation” you passed into the method as the first argument

- Polls until there has been at least one recorded “sent” tracked message and all outstanding “sent” messages have been logged as completely handled or until the configured timeout period has expired.

- Returns a boolean that just indicates whether or not MessageHistory finished successfully (true) or just timed out (false).

For the pedants and the truly interested among us, the WaitForWorkToFinish() method is an example of using Continuation Passing Style (CPS) to correctly order the execution steps. I would argue that CPS is very useful in these kinds of scenarios where you have a set order of execution but some step in the middle or end can vary.

Visualizing What the Heck Just Happened

The next big challenge in testing message-based, service bus applications is being able to understand what is really happening inside the system when one of these big end to end tests fails. There’s asynchronous behavior and loosely coupled publish/subscribe mechanics. It’s clearly not the easiest problem domain to troubleshoot when things don’t work the way you expect.

We have partially solved this problem by tying the semantic log messages produced by FubuMVC’s service bus system into the results report of our automated tests. Specifically, we use the Storyteller 3 project (one of my other OSS projects that is being criminally neglected because Marten is so busy) as our end to end test harness. One of the powerful features in Storyteller 3 is the ability to publish and embed custom diagnostics into the HTML results report that Storyteller produces.

Building on the MessageRecordListener setup in the previous section, FubuMVC will log all of the service bus activity to an internal history. In our Storyteller test harness, we wipe out the existing state of the recorded logging messages before the test executes, then at the end of the specification run we gather all of the recorded logging messages for just that test run and inject some custom HTML into the test results.

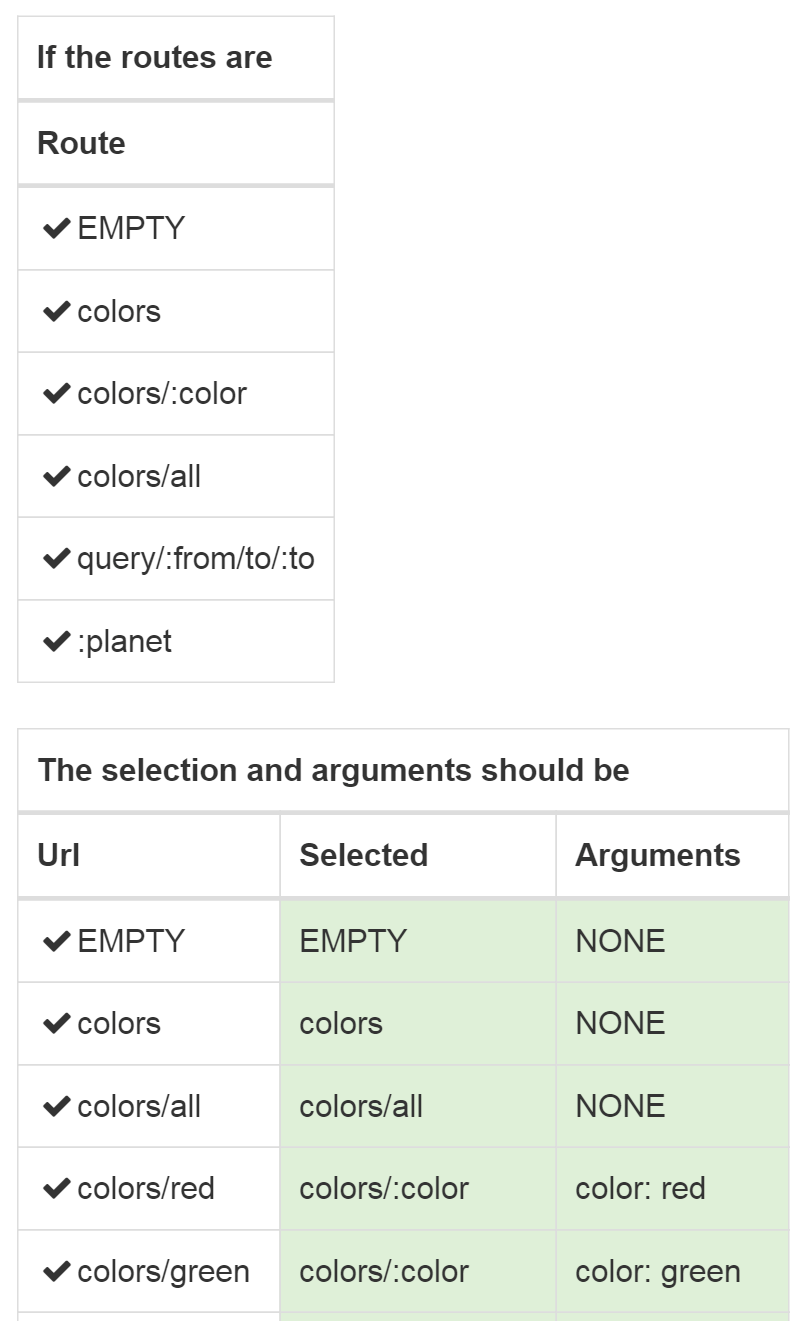

We do two different visualizations, a “threaded” message history arranged by the history of a single message, who published it, who handled it, and what became of it?

The threaded history view helps to understand how a single message was processed from sender, to receiver, to execution. Any error steps will show up in the threaded history. So will retry attempts and any additional messages triggered by the topmost message.

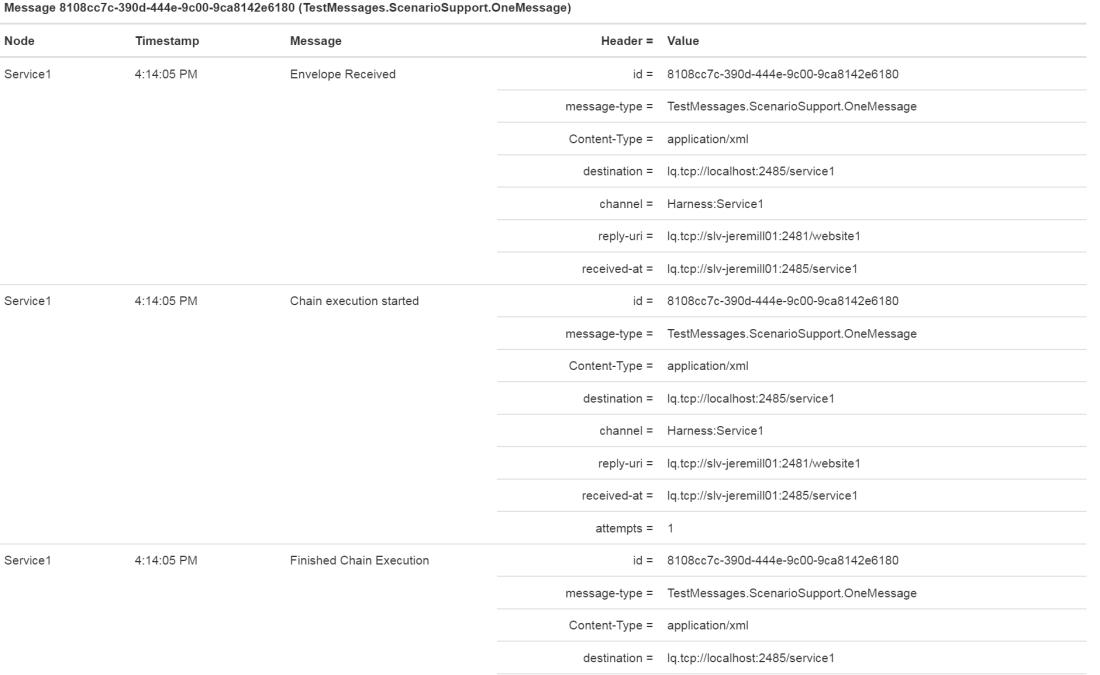

We also present pretty well the same information in a tabular form that exposes the metadata for the message envelope wrapper at every point some activity is recorded:

I’m using images for the blog post, but these reports are written into the Storyteller HTML results. These diagnostics have been invaluable to us in understanding how our message based systems actually behave. Having these diagnostics as part of the test results on the CI server has been very helpful in diagnosing failures in the CI builds that can be notoriously hard to debug.

Next time…

At some point I’ll blog about how we integrate FubuMVC’s HTTP diagnostics into the Storyteller results and maybe a different post about the performance tracking data that Storyteller exposes as part of the testing results. But don’t look for any of that too soon;)