JasperFx Software is open for business and offering consulting services (like helping you craft modular monolith strategies!) and support contracts for both Marten and Wolverine so you know you can feel secure taking a big technical bet on these tools and reap all the advantages they give for productive and maintainable server side .NET development.

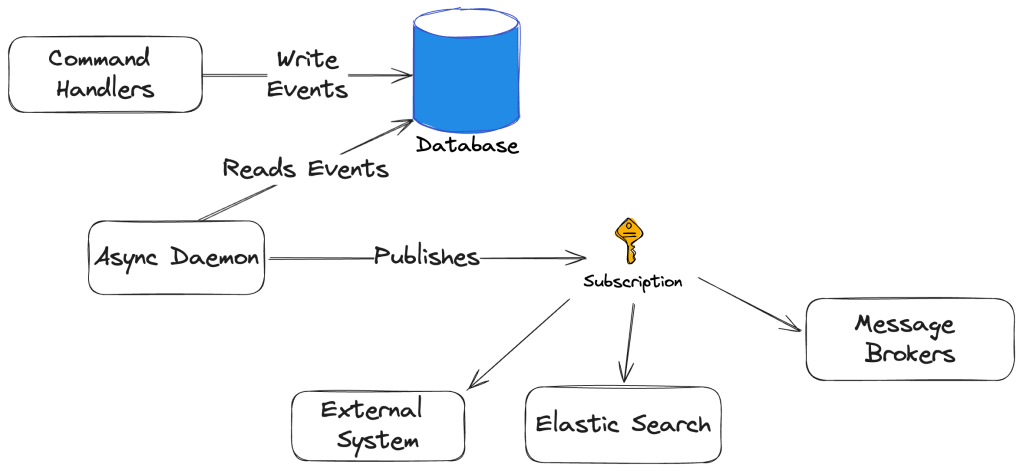

As a follow on post from First Class Event Subscriptions in Marten last week, let’s introduce Wolverine into the mix for end to end Event Driven Architecture approaches. Using Wolverine’s new Event Subscriptions model, “Critter Stack” systems can automatically process Marten event data with Wolverine message handlers:

If all we want to do is publish Marten event data through Wolverine’s message publishing (which remember, can be either to local queues or external message brokers), we have this simple recipe:

using var host = await Host.CreateDefaultBuilder()

.UseWolverine(opts =>

{

opts.Services

.AddMarten()

// Just pulling the connection information from

// the IoC container at runtime.

.UseNpgsqlDataSource()

// You don't absolutely have to have the Wolverine

// integration active here for subscriptions, but it's

// more than likely that you will want this anyway

.IntegrateWithWolverine()

// The Marten async daemon most be active

.AddAsyncDaemon(DaemonMode.HotCold)

// This would attempt to publish every non-archived event

// from Marten to Wolverine subscribers

.PublishEventsToWolverine("Everything")

// You wouldn't do this *and* the above option, but just to show

// the filtering

.PublishEventsToWolverine("Orders", relay =>

{

// Filtering

relay.FilterIncomingEventsOnStreamType(typeof(Order));

// Optionally, tell Marten to only subscribe to new

// events whenever this subscription is first activated

relay.Options.SubscribeFromPresent();

});

}).StartAsync();

First off, what’s a “subscriber?” That would mean any event that Wolverine recognizes as having:

- A local message handler in the application for the specific event type, which would effectively direct Wolverine to publish the event data to a local queue

- A local message handler in the application for the specific

IEvent<T>type, which would effectively direct Wolverine to publish the event with itsIEventMarten metadata wrapper to a local queue - Any event type where Wolverine can discover subscribers through routing rules

All the Wolverine subscription is doing is effectively calling IMessageBus.PublishAsync() against the event data or the IEvent<T> wrapper. You can make the subscription run more efficiently by applying event or stream type filters for the subscription.

If you need to do a transformation of the raw IEvent<T> or the internal event type to some kind of external event type for publishing to external systems when you want to avoid directly coupling other subscribers to your system’s internals, you can accomplish that by just building a message handler that does the transformation and publishes a cascading message like so:

public record OrderCreated(string OrderNumber, Guid CustomerId);

// I wouldn't use this kind of suffix in real life, but it helps

// document *what* this is for the sample in the docs:)

public record OrderCreatedIntegrationEvent(string OrderNumber, string CustomerName, DateTimeOffset Timestamp);

// We're going to use the Marten IEvent metadata and some other Marten reference

// data to transform the internal OrderCreated event

// to an OrderCreatedIntegrationEvent that will be more appropriate for publishing to

// external systems

public static class InternalOrderCreatedHandler

{

public static Task<Customer?> LoadAsync(IEvent<OrderCreated> e, IQuerySession session,

CancellationToken cancellationToken)

=> session.LoadAsync<Customer>(e.Data.CustomerId, cancellationToken);

public static OrderCreatedIntegrationEvent Handle(IEvent<OrderCreated> e, Customer customer)

{

return new OrderCreatedIntegrationEvent(e.Data.OrderNumber, customer.Name, e.Timestamp);

}

}

Process Events as Messages in Strict Order

In some cases you may want the events to be executed by Wolverine message handlers in strict order. With the recipe below:

using var host = await Host.CreateDefaultBuilder()

.UseWolverine(opts =>

{

opts.Services

.AddMarten(o =>

{

// This is the default setting, but just showing

// you that Wolverine subscriptions will be able

// to skip over messages that fail without

// shutting down the subscription

o.Projections.Errors.SkipApplyErrors = true;

})

// Just pulling the connection information from

// the IoC container at runtime.

.UseNpgsqlDataSource()

// You don't absolutely have to have the Wolverine

// integration active here for subscriptions, but it's

// more than likely that you will want this anyway

.IntegrateWithWolverine()

// The Marten async daemon most be active

.AddAsyncDaemon(DaemonMode.HotCold)

// Notice the allow list filtering of event types and the possibility of overriding

// the starting point for this subscription at runtime

.ProcessEventsWithWolverineHandlersInStrictOrder("Orders", o =>

{

// It's more important to create an allow list of event types that can be processed

o.IncludeType<OrderCreated>();

// Optionally mark the subscription as only starting from events from a certain time

o.Options.SubscribeFromTime(new DateTimeOffset(new DateTime(2023, 12, 1)));

});

}).StartAsync();

In this recipe, Marten & Wolverine are working together to call IMessageBus.InvokeAsync() on each event in order. You can use both the actual event type (OrderCreated) or the wrapped Marten event type (IEvent<OrderCreated>) as the message type for your message handler.

In the case of exceptions from processing the event with Wolverine:

- Any built in “retry” error handling will kick in to retry the event processing inline

- If the retries are exhausted, and the Marten setting for

StoreOptions.Projections.Errors.SkipApplyErrorsistrue, Wolverine will persist the event to its PostgreSQL backed dead letter queue and proceed to the next event. This setting is the default with Marten when the daemon is running continuously in the background, butfalsein rebuilds or replays - If the retries are exhausted, and

SkipApplyErrors = false, Wolverine will tell Marten to pause the subscription at the last event sequence that succeeded

Custom, Batched Subscriptions

The base type for all Wolverine subscriptions is the Wolverine.Marten.Subscriptions.BatchSubscription class. If you need to do something completely custom, or just to take action on a batch of events at one time, subclass that type. Here is an example usage where I’m using event carried state transfer to publish batches of reference data about customers being activated or deactivated within our system:

public record CompanyActivated(string Name);

public record CompanyDeactivated();

public record NewCompany(Guid Id, string Name);

// Message type we're going to publish to external

// systems to keep them up to date on new companies

public class CompanyActivations

{

public List<NewCompany> Additions { get; set; } = new();

public List<Guid> Removals { get; set; } = new();

public void Add(Guid companyId, string name)

{

Removals.Remove(companyId);

// Fill is an extension method in JasperFx.Core that adds the

// record to a list if the value does not already exist

Additions.Fill(new NewCompany(companyId, name));

}

public void Remove(Guid companyId)

{

Removals.Fill(companyId);

Additions.RemoveAll(x => x.Id == companyId);

}

}

public class CompanyTransferSubscription : BatchSubscription

{

public CompanyTransferSubscription() : base("CompanyTransfer")

{

IncludeType<CompanyActivated>();

IncludeType<CompanyDeactivated>();

}

public override async Task ProcessEventsAsync(EventRange page, ISubscriptionController controller, IDocumentOperations operations,

IMessageBus bus, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var activations = new CompanyActivations();

foreach (var e in page.Events)

{

switch (e)

{

// In all cases, I'm assuming that the Marten stream id is the identifier for a customer

case IEvent<CompanyActivated> activated:

activations.Add(activated.StreamId, activated.Data.Name);

break;

case IEvent<CompanyDeactivated> deactivated:

activations.Remove(deactivated.StreamId);

break;

}

}

// At the end of all of this, publish a single message

// In case you're wondering, this will opt into Wolverine's

// transactional outbox with the same transaction as any changes

// made by Marten's IDocumentOperations passed in, including Marten's

// own work to track the progression of this subscription

await bus.PublishAsync(activations);

}

}

And the related code to register this subscription:

using var host = await Host.CreateDefaultBuilder()

.UseWolverine(opts =>

{

opts.UseRabbitMq();

// There needs to be *some* kind of subscriber for CompanyActivations

// for this to work at all

opts.PublishMessage<CompanyActivations>()

.ToRabbitExchange("activations");

opts.Services

.AddMarten()

// Just pulling the connection information from

// the IoC container at runtime.

.UseNpgsqlDataSource()

.IntegrateWithWolverine()

// The Marten async daemon most be active

.AddAsyncDaemon(DaemonMode.HotCold)

// Register the new subscription

.SubscribeToEvents(new CompanyTransferSubscription());

}).StartAsync();

Summary

The feature set shown here has been a very long planned set of capabilities to truly extend the “Critter Stack” into the realm of supporting Event Driven Architecture approaches from soup to nuts. Using the Wolverine subscriptions automatically gets you support to publish Marten events to any transport supported by Wolverine itself, and does so in a much more robust way than you can easily roll by hand like folks did previously with Marten’s IProjection interface. I’m currently helping a JasperFx Software client utilize this functionality for data exchange that has strict ordering and at least once delivery guarantees.