Hey, did you know that JasperFx Software is ready for formal support plans for Marten and Wolverine? Not only are we trying to make the “Critter Stack” tools be viable long term options for your shop, we’re also interested in hearing your opinions about the tools and how they should change. We’re also certainly open to help you succeed with your software development projects on a consulting basis whether you’re using any part of the Critter Stack or any other .NET server side tooling.

Let’s build a small web service application using the whole “Critter Stack” and their friends, one small step at a time. For right now, the “finished” code is at CritterStackHelpDesk on GitHub.

The posts in this series are:

- Event Storming

- Marten as Event Store

- Marten Projections

- Integrating Marten into Our Application

- Wolverine as Mediator

- Web Service Query Endpoints with Marten

- Dealing with Concurrency

- Wolverine’s Aggregate Handler Workflow FTW!

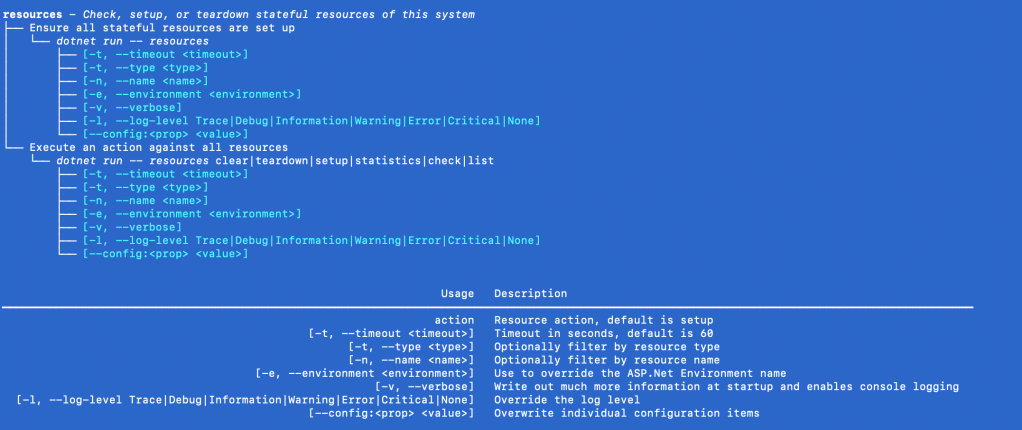

- Command Line Diagnostics with Oakton

- Integration Testing Harness

- Marten as Document Database

- Asynchronous Processing with Wolverine

- Durable Outbox Messaging and Why You Care!

- Wolverine HTTP Endpoints (this post)

- Easy Unit Testing with Pure Functions

- Vertical Slice Architecture

- Messaging with Rabbit MQ

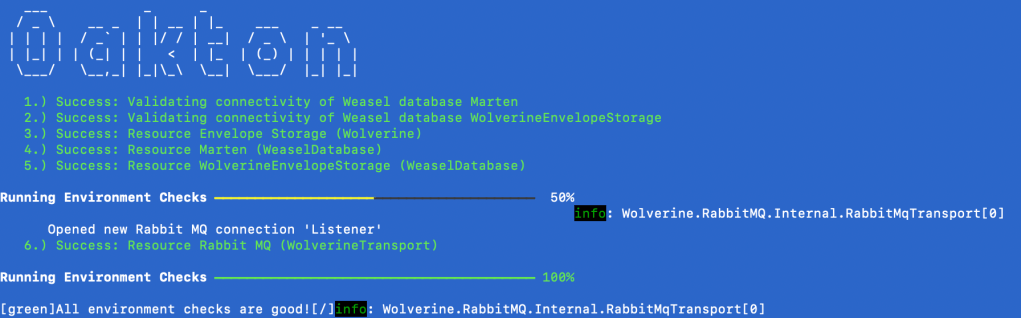

- The “Stateful Resource” Model

- Resiliency

Heretofore in this series, I’ve been using ASP.Net MVC Core controllers anytime we’ve had to build HTTP endpoints for our incident tracking, help desk system in order to introduce new concepts a little more slowly.

If you would, let’s refer back to an earlier incarnation of an HTTP endpoint to handle our LogIncident command from an earlier post in this series:

public class IncidentController : ControllerBase

{

private readonly IDocumentSession _session;

public IncidentController(IDocumentSession session)

{

_session = session;

}

[HttpPost("/api/incidents")]

public async Task<IResult> Log(

[FromBody] LogIncident command

)

{

var userId = currentUserId();

var logged = new IncidentLogged(command.CustomerId, command.Contact, command.Description, userId);

var incidentId = _session.Events.StartStream(logged).Id;

await _session.SaveChangesAsync(HttpContext.RequestAborted);

return Results.Created("/incidents/" + incidentId, incidentId);

}

private Guid currentUserId()

{

// let's say that we do something here that "finds" the

// user id as a Guid from the ClaimsPrincipal

var userIdClaim = User.FindFirst("user-id");

if (userIdClaim != null && Guid.TryParse(userIdClaim.Value, out var id))

{

return id;

}

throw new UnauthorizedAccessException("No user");

}

}

Just to be clear as possible here, the Wolverine HTTP endpoints feature introduced in this post can be mixed and matched with MVC Core and/or Minimal API or even FastEndpoints within the same application and routing tree. I think the ASP.Net team deserves some serious credit for making that last sentence a fact.

Today though, let’s use Wolverine HTTP endpoints and rewrite that controller method above the “Wolverine way.” To get started, add a Nuget reference to the help desk service like so:

dotnet add package WolverineFx.Http

Next, let’s break into our Program file and add Wolverine endpoints to our routing tree near the bottom of the file like so:

app.MapWolverineEndpoints(opts =>

{

// We'll add a little more in a bit...

});

// Just to show where the above code is within the context

// of the Program file...

return await app.RunOaktonCommands(args);

Now, let’s make our first cut at a Wolverine HTTP endpoint for the LogIncident command, but I’m purposely going to do it without introducing a lot of new concepts, so please bear with me a bit:

public record NewIncidentResponse(Guid IncidentId)

: CreationResponse("/api/incidents/" + IncidentId);

public static class LogIncidentEndpoint

{

[WolverinePost("/api/incidents")]

public static NewIncidentResponse Post(

// No [FromBody] stuff necessary

LogIncident command,

// Service injection is automatic,

// just like message handlers

IDocumentSession session,

// You can take in an argument for HttpContext

// or immediate members of HttpContext

// as method arguments

ClaimsPrincipal principal)

{

// Some ugly code to find the user id

// within a claim for the currently authenticated

// user

Guid userId = Guid.Empty;

var userIdClaim = principal.FindFirst("user-id");

if (userIdClaim != null && Guid.TryParse(userIdClaim.Value, out var claimValue))

{

userId = claimValue;

}

var logged = new IncidentLogged(command.CustomerId, command.Contact, command.Description, userId);

var id = session.Events.StartStream<Incident>(logged).Id;

return new NewIncidentResponse(id);

}

}

Here’s a few salient facts about the code above to explain what it’s doing:

- The

[WolverinePost]attribute tells Wolverine that hey, this method is an HTTP handler, and Wolverine will discover this method and add it to the application’s endpoint routing tree at bootstrapping time. - Just like Wolverine message handlers, the endpoint methods are flexible and Wolverine generates code around your code to mediate between the raw

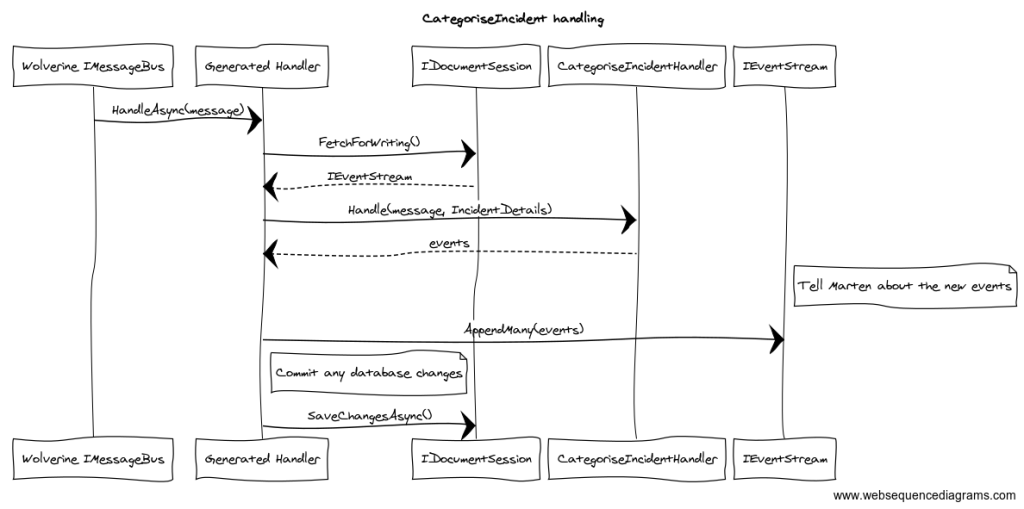

HttpContextfor the request and your code - We have already enabled Marten transactional middleware for our message handlers in an earlier post, and that happily applies to Wolverine HTTP endpoints as well. That helps make our endpoint method be just a synchronous method with the transactional middleware dealing with the ugly asynchronous stuff for us.

- You can “inject”

HttpContextand its immediate children into the method signatures as I did with theClaimsPrincipalup above - Method injection is automatic without any silly

[FromServices]attributes, and that’s what’s happening with theIDocumentSessionargument - The

LogIncidentparameter is assumed to be the HTTP request body due to being the first argument, and it will be deserialized from the incoming JSON in the request body just like you’d probably expect - The

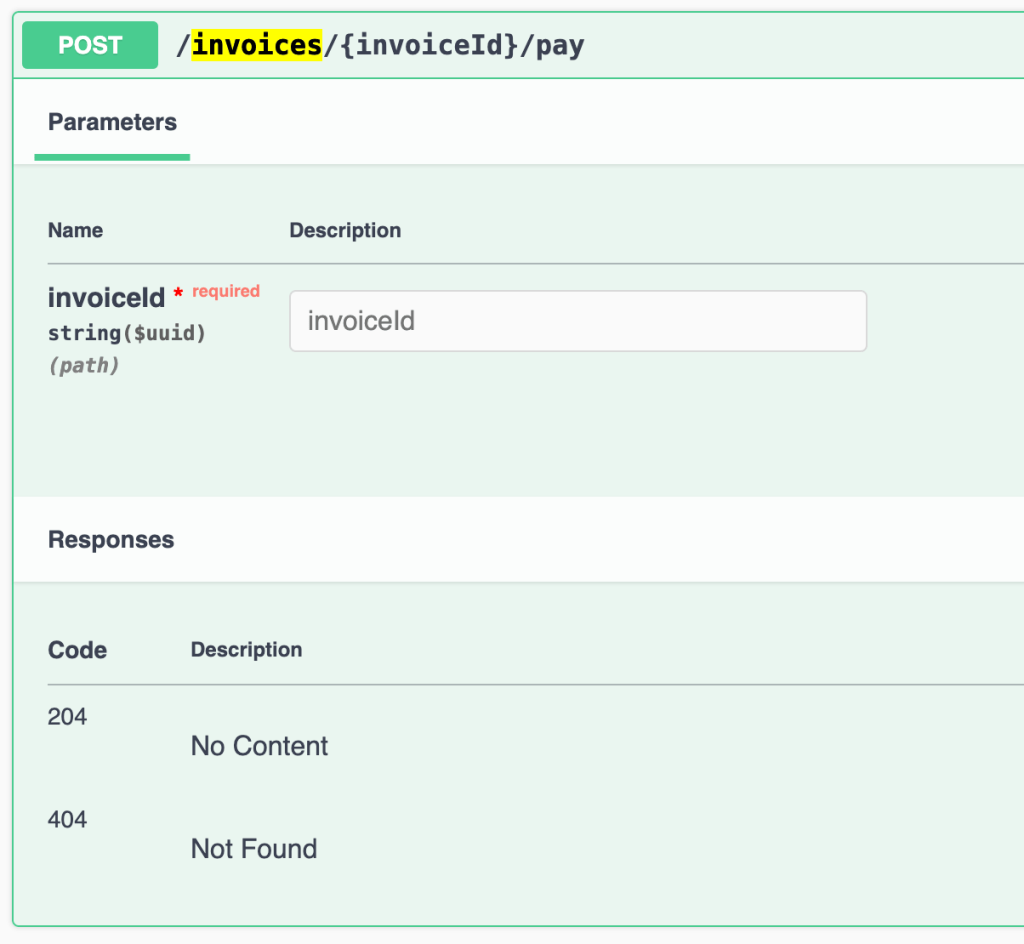

NewIncidentResponsetype is roughly the equivalent to usingResults.Created()in Minimal API to create a response body with the url of the newly createdIncidentstream and an HTTP status code of 201 for “Created.” What’s different about Wolverine.HTTP is that it can infer OpenAPI documentation from the signature of that type without requiring you to pollute your code by manually adding[ProducesResponseType]attributes on the method to get a “proper” OpenAPI document for the endpoint.

Moving on, that user id detection from the ClaimsPrincipal looks a little bit ugly to me, and likely to be repetitive. Let’s ameliorate that by introducing Wolverine’s flavor of HTTP middleware and move that code to this class:

// Using the custom type makes it easier

// for the Wolverine code generation to route

// things around. I'm not ashamed.

public record User(Guid Id);

public static class UserDetectionMiddleware

{

public static (User, ProblemDetails) Load(ClaimsPrincipal principal)

{

var userIdClaim = principal.FindFirst("user-id");

if (userIdClaim != null && Guid.TryParse(userIdClaim.Value, out var id))

{

// Everything is good, keep on trucking with this request!

return (new User(id), WolverineContinue.NoProblems);

}

// Nope, nope, nope. We got problems, so stop the presses and emit a ProblemDetails response

// with a 400 status code telling the caller that there's no valid user for this request

return (new User(Guid.Empty), new ProblemDetails { Detail = "No valid user", Status = 400});

}

}

Do note the usage of ProblemDetails in that middleware. If there is no user-id claim on the ClaimsPrincipal, we’ll abort the request by writing out the ProblemDetails stating there’s no valid user. This pattern is baked into Wolverine.HTTP to help create one off request validations. We’ll utilize this quite a bit more later.

Next, I need to add that new bit of middleware to our application. As a shortcut, I’m going to just add it to every single Wolverine HTTP endpoint by breaking back into our Program file and adding this line of code:

app.MapWolverineEndpoints(opts =>

{

// We'll add a little more in a bit...

// Creates a User object in HTTP requests based on

// the "user-id" claim

opts.AddMiddleware(typeof(UserDetectionMiddleware));

});

Now, back to our endpoint code and I’ll take advantage of that middleware by changing the method to this:

[WolverinePost("/api/incidents")]

public static NewIncidentResponse Post(

// No [FromBody] stuff necessary

LogIncident command,

// Service injection is automatic,

// just like message handlers

IDocumentSession session,

// This will be created for us through the new user detection

// middleware

User user)

{

var logged = new IncidentLogged(

command.CustomerId,

command.Contact,

command.Description,

user.Id);

var id = session.Events.StartStream<Incident>(logged).Id;

return new NewIncidentResponse(id);

}

This is a little bit of a bonus, but let’s also get rid of the need to inject the Marten IDocumentSession service by using a Wolverine “side effect” with this equivalent code:

[WolverinePost("/api/incidents")]

public static (NewIncidentResponse, IStartStream) Post(LogIncident command, User user)

{

var logged = new IncidentLogged(

command.CustomerId,

command.Contact,

command.Description,

user.Id);

var op = MartenOps.StartStream<Incident>(logged);

return (new NewIncidentResponse(op.StreamId), op);

}

In the code above I’m using the MartenOps.StartStream() method to return a “side effect” that will create a new Marten stream as part of the request instead of directly interacting with the IDocumentSession from Marten. That’s a small thing you might not care for, but it can lead to the elimination of mock objects within your unit tests as you can now write a state-based test directly against the method above like so:

public class LogIncident_handling

{

[Fact]

public void handle_the_log_incident_command()

{

// This is trivial, but the point is that

// we now have a pure function that can be

// unit tested by pushing inputs in and measuring

// outputs without any pesky mock object setup

var contact = new Contact(ContactChannel.Email);

var theCommand = new LogIncident(BaselineData.Customer1Id, contact, "It's broken");

var theUser = new User(Guid.NewGuid());

var (_, stream) = LogIncidentEndpoint.Post(theCommand, theUser);

// Test the *decision* to emit the correct

// events and make sure all that pesky left/right

// hand mapping is correct

var logged = stream.Events.Single()

.ShouldBeOfType<IncidentLogged>();

logged.CustomerId.ShouldBe(theCommand.CustomerId);

logged.Contact.ShouldBe(theCommand.Contact);

logged.LoggedBy.ShouldBe(theUser.Id);

}

}

Hey, let’s add some validation too!

We’ve already introduced middleware, so let’s just incorporate the popular Fluent Validation library into our project and let it do some basic validation on the incoming LogIncident command body, and if any validation fails, pull the ripcord and parachute out of the request with a ProblemDetails body and 400 status code that describes the validation errors.

Let’s add that in by first adding some pre-packaged middleware for Wolverine.HTTP with:

dotnet add package WolverineFx.Http.FluentValidation

Next, I have to add the usage of that middleware through this new line of code:

app.MapWolverineEndpoints(opts =>

{

// Direct Wolverine.HTTP to use Fluent Validation

// middleware to validate any request bodies where

// there's a known validator (or many validators)

opts.UseFluentValidationProblemDetailMiddleware();

// Creates a User object in HTTP requests based on

// the "user-id" claim

opts.AddMiddleware(typeof(UserDetectionMiddleware));

});

And add an actual validator for our LogIncident, and in this case that model is just an internal concern of our service, so I’ll just embed that new validator as an inner type of the command type like so:

public record LogIncident(

Guid CustomerId,

Contact Contact,

string Description

)

{

public class LogIncidentValidator : AbstractValidator<LogIncident>

{

// I stole this idea of using inner classes to keep them

// close to the actual model from *someone* online,

// but don't remember who

public LogIncidentValidator()

{

RuleFor(x => x.Description).NotEmpty().NotNull();

RuleFor(x => x.Contact).NotNull();

}

}

};

Now, Wolverine does have to “know” about these validators to use them within the endpoint handling, so I’ll need to have these types registered in the application’s IoC container against the right IValidator<T> interface. This is not required, but Wolverine has a (Lamar) helper to find and register these validators within your project and do so in a way that’s most efficient at runtime (i.e., there’s a micro optimization for making these validators have a Singleton life time in the container if Wolverine can see that the types are stateless). I’ll use that little helper in our Program file within the UseWolverine() configuration like so:

builder.Host.UseWolverine(opts =>

{

// lots more stuff unfortunately, but focus on the line below

// just for now:-)

// Apply the validation middleware *and* discover and register

// Fluent Validation validators

opts.UseFluentValidation();

}

And that’s that. We’ve not got Fluent Validation validation in the request handling for the LogIncident command. In a later section, I’ll explain how Wolverine does this, and try to sell you all on the idea that Wolverine is able to do this more efficiently than other commonly used frameworks *cough* MediatR *cough* that depend on conditional runtime code.

One off validation with “Compound Handlers”

As you might have noticed, the LogIncident command has a CustomerId property that we’re using as is within our HTTP handler. We should never just trust the inputs of a random client, so let’s at least validate that the command refers to a real customer.

Now, typically I like to make Wolverine message handler or HTTP endpoint methods be the “happy path” and handle exception cases and one off validations with a Wolverine feature we inelegantly call “compound handlers.”

I’m going to add a new method to our LogIncidentHandler class like so:

// Wolverine has some naming conventions for Before/Load

// or After/AfterAsync, but you can use a more descriptive

// method name and help Wolverine out with an attribute

[WolverineBefore]

public static async Task<ProblemDetails> ValidateCustomer(

LogIncident command,

// Method injection works just fine within middleware too

IDocumentSession session)

{

var exists = await session.Query<Customer>().AnyAsync(x => x.Id == command.CustomerId);

return exists

? WolverineContinue.NoProblems

: new ProblemDetails { Detail = $"Unknown customer id {command.CustomerId}", Status = 400};

}

Integration Testing

While the individual methods and middleware can all be tested separately, you do want to put everything together with an integration test to prove out whether or not all this magic really works. As I described in an earlier post where we learned how to use Alba to create an integration testing harness for a “critter stack” application, we can write an end to end integration test against the HTTP endpoint like so (this sample doesn’t cover every permutation, but hopefully you get the point):

[Fact]

public async Task create_a_new_incident_happy_path()

{

// We'll need a user

var user = new User(Guid.NewGuid());

// Log a new incident first

var initial = await Scenario(x =>

{

var contact = new Contact(ContactChannel.Email);

x.Post.Json(new LogIncident(BaselineData.Customer1Id, contact, "It's broken")).ToUrl("/api/incidents");

x.StatusCodeShouldBe(201);

x.WithClaim(new Claim("user-id", user.Id.ToString()));

});

var incidentId = initial.ReadAsJson<NewIncidentResponse>().IncidentId;

using var session = Store.LightweightSession();

var events = await session.Events.FetchStreamAsync(incidentId);

var logged = events.First().ShouldBeOfType<IncidentLogged>();

// This deserves more assertions, but you get the point...

logged.CustomerId.ShouldBe(BaselineData.Customer1Id);

}

[Fact]

public async Task log_incident_with_invalid_customer()

{

// We'll need a user

var user = new User(Guid.NewGuid());

// Reject the new incident because the Customer for

// the command cannot be found

var initial = await Scenario(x =>

{

var contact = new Contact(ContactChannel.Email);

var nonExistentCustomerId = Guid.NewGuid();

x.Post.Json(new LogIncident(nonExistentCustomerId, contact, "It's broken")).ToUrl("/api/incidents");

x.StatusCodeShouldBe(400);

x.WithClaim(new Claim("user-id", user.Id.ToString()));

});

}

}

Um, how does this all work?

So far I’ve shown you some “magic” code, and that tends to really upset some folks. I also made some big time claims about how Wolverine is able to be more efficient at runtime (alas, there is a significant “cold start” problem you can easily work around, so don’t get upset if your first ever Wolverine request isn’t snappy).

Wolverine works by using code generation to wrap its handling code around your code. That includes the middleware, and the usage of any IoC services as well. Moreover, do you know what the fastest IoC container is in all the .NET land? I certainly think that Lamar is at least in the game for that one, but nope, the answer is no IoC container at runtime.

One of the advantages of this approach is that we can preview the generated code to unravel the “magic” and explain what Wolverine is doing at runtime. Moreover, we’ve tried to add descriptive comments to the generated code to further explain what and why code is in place.

See more about this in my post Unraveling the Magic in Wolverine.

Here’s the generated code for our LogIncident endpoint (warning, ugly generated code ahead):

// <auto-generated/>

#pragma warning disable

using FluentValidation;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Routing;

using System;

using System.Linq;

using Wolverine.Http;

using Wolverine.Http.FluentValidation;

using Wolverine.Marten.Publishing;

using Wolverine.Runtime;

namespace Internal.Generated.WolverineHandlers

{

// START: POST_api_incidents

public class POST_api_incidents : Wolverine.Http.HttpHandler

{

private readonly Wolverine.Http.WolverineHttpOptions _wolverineHttpOptions;

private readonly Wolverine.Runtime.IWolverineRuntime _wolverineRuntime;

private readonly Wolverine.Marten.Publishing.OutboxedSessionFactory _outboxedSessionFactory;

private readonly FluentValidation.IValidator<Helpdesk.Api.LogIncident> _validator;

private readonly Wolverine.Http.FluentValidation.IProblemDetailSource<Helpdesk.Api.LogIncident> _problemDetailSource;

public POST_api_incidents(Wolverine.Http.WolverineHttpOptions wolverineHttpOptions, Wolverine.Runtime.IWolverineRuntime wolverineRuntime, Wolverine.Marten.Publishing.OutboxedSessionFactory outboxedSessionFactory, FluentValidation.IValidator<Helpdesk.Api.LogIncident> validator, Wolverine.Http.FluentValidation.IProblemDetailSource<Helpdesk.Api.LogIncident> problemDetailSource) : base(wolverineHttpOptions)

{

_wolverineHttpOptions = wolverineHttpOptions;

_wolverineRuntime = wolverineRuntime;

_outboxedSessionFactory = outboxedSessionFactory;

_validator = validator;

_problemDetailSource = problemDetailSource;

}

public override async System.Threading.Tasks.Task Handle(Microsoft.AspNetCore.Http.HttpContext httpContext)

{

var messageContext = new Wolverine.Runtime.MessageContext(_wolverineRuntime);

// Building the Marten session

await using var documentSession = _outboxedSessionFactory.OpenSession(messageContext);

// Reading the request body via JSON deserialization

var (command, jsonContinue) = await ReadJsonAsync<Helpdesk.Api.LogIncident>(httpContext);

if (jsonContinue == Wolverine.HandlerContinuation.Stop) return;

// Execute FluentValidation validators

var result1 = await Wolverine.Http.FluentValidation.Internals.FluentValidationHttpExecutor.ExecuteOne<Helpdesk.Api.LogIncident>(_validator, _problemDetailSource, command).ConfigureAwait(false);

// Evaluate whether or not the execution should be stopped based on the IResult value

if (!(result1 is Wolverine.Http.WolverineContinue))

{

await result1.ExecuteAsync(httpContext).ConfigureAwait(false);

return;

}

(var user, var problemDetails2) = Helpdesk.Api.UserDetectionMiddleware.Load(httpContext.User);

// Evaluate whether the processing should stop if there are any problems

if (!(ReferenceEquals(problemDetails2, Wolverine.Http.WolverineContinue.NoProblems)))

{

await WriteProblems(problemDetails2, httpContext).ConfigureAwait(false);

return;

}

var problemDetails3 = await Helpdesk.Api.LogIncidentEndpoint.ValidateCustomer(command, documentSession).ConfigureAwait(false);

// Evaluate whether the processing should stop if there are any problems

if (!(ReferenceEquals(problemDetails3, Wolverine.Http.WolverineContinue.NoProblems)))

{

await WriteProblems(problemDetails3, httpContext).ConfigureAwait(false);

return;

}

// The actual HTTP request handler execution

(var newIncidentResponse_response, var startStream) = Helpdesk.Api.LogIncidentEndpoint.Post(command, user);

// Placed by Wolverine's ISideEffect policy

startStream.Execute(documentSession);

// This response type customizes the HTTP response

ApplyHttpAware(newIncidentResponse_response, httpContext);

// Commit any outstanding Marten changes

await documentSession.SaveChangesAsync(httpContext.RequestAborted).ConfigureAwait(false);

// Have to flush outgoing messages just in case Marten did nothing because of https://github.com/JasperFx/wolverine/issues/536

await messageContext.FlushOutgoingMessagesAsync().ConfigureAwait(false);

// Writing the response body to JSON because this was the first 'return variable' in the method signature

await WriteJsonAsync(httpContext, newIncidentResponse_response);

}

}

// END: POST_api_incidents

}

Summary and What’s Next

The Wolverine.HTTP library was originally built to be a supplement to MVC Core or Minimal API by allowing you to create endpoints that integrated well into Wolverine’s messaging, transactional outbox functionality, and existing transactional middleware. It has since grown into being more of a full fledged alternative for building web services, but with potential for substantially less ceremony and far more testability than MVC Core.

In later posts I’ll talk more about the runtime architecture and how Wolverine squeezes out more performance by eliminating conditional runtime switching, reducing object allocations, and sidestepping the dictionary lookups that are endemic to other “flexible” .NET frameworks like MVC Core.

Wolverine.HTTP has not yet been used with Razor at all, and I’m not sure that will ever happen. Not to worry though, you can happily use Wolverine.HTTP in the same application with MVC Core controllers or even Minimal API endpoints.

OpenAPI support has been a constant challenge with Wolverine.HTTP as the OpenAPI generation in ASP.Net Core is very MVC-centric, but I think we’re in much better shape now.

In the next post, I think we’ll introduce asynchronous messaging with Rabbit MQ. At some point in this series I’m going to talk more about how the “Critter Stack” is well suited for a lower ceremony vertical slice architecture that (hopefully) creates a maintainable and testable codebase without all the typical Clean/Onion Architecture baggage that I could personally do without.

And just for fun…

My “History” with ASP.Net MVC

There’s no useful content in this section, just some navel-gazing. Even though I really haven’t had to use ASP.Net MVC too terribly much, I do have a long history with it:

- In the beginning, there was what we now call ASP Classic, and it was good. For that day and time anyway when we would happily code directly in production and before TDD and SOLID and namby-pamby “source control.” (I started my development career in “Shadow IT” if that’s not obvious here). And when we did use source control, it was VSS because on the sly because the official source control in the office was something far, far worse that was COBOL-centric that I don’t think even exists any longer.

- Next there was ASP.Net WebForms and it was dreadful. I hated it.

- We started collectively learning about Agile and wanted to practice Test Driven Development, and began to hate WebForms even more

- Ruby on Rails came out in the middle 00’s and made what later became the ALT.Net community absolutely loathe WebForms even more than we already did

- At an MVP Summit on the Microsoft campus, the one and only Scott Guthrie, the Gu himself, showed a very early prototype of ASP.Net MVC to a handful of us and I was intrigued. That continued onward through the official unveiling of MVC at the very first ALT.Net open spaces event in Austin in ’07.

- A few collaborators and I decided that early ASP.Net MVC was too high ceremony and went all “Captain Ahab” trying to make an alternative, open source framework called FubuMVC go as an alternative — all while NancyFx, a “yet another Sinatra clone” became far more successful years before Microsoft finally got around to their own inevitable Sinatra clone (Minimal API)

- After .NET Core came along and made .NET a helluva lot better ecosystem, I decided that whatever, MVC Core is fine, it’s not going to be the biggest problem on our project, and if the client wants to use it, there’s no need to be upset about it. It’s fine, no really.

- MVC Core has gotten some incremental improvements over time that made it lower ceremony than earlier ASP.Net MVC, and that’s worth calling out as a positive

- People working with MVC Core started running into the problem of bloated controllers, and started using early MediatR as a way to kind of, sort of manage controller bloat by offloading it into focused command handlers. I mocked that approach mercilessly, but that was partially because of how awful a time I had helping folks do absurdly complicated middleware schemes with MediatR using StructureMap or Lamar (MVC Core + MediatR is probably worthwhile as a forcing function to avoid the controller bloat problems with MVC Core by itself)

- I worked on several long-running codebases built with MVC Core based on Clean Architecture templates that were ginormous piles of technical debt, and I absolutely blame MVC Core as a contributing factor for that

- I’m back to mildly disliking MVC Core (and I’m outright hostile to Clean/Onion templates). Not that you can’t write maintainable systems with MVC Core, but I think that its idiomatic usage can easily lead to unmaintainable systems. Let’s just say that I don’t think that MVC Core — and especially combined with some kind of Clean/Onion Architecture template as it very commonly is out in the wild — leads folks to the “pit of success” in the long run